An alternative equitable future can exist only after we acknowledge the deeply colonial and divided nature of thinking that society currently dwells in and act to create an open, interoperable, and accountable system.

Boundary

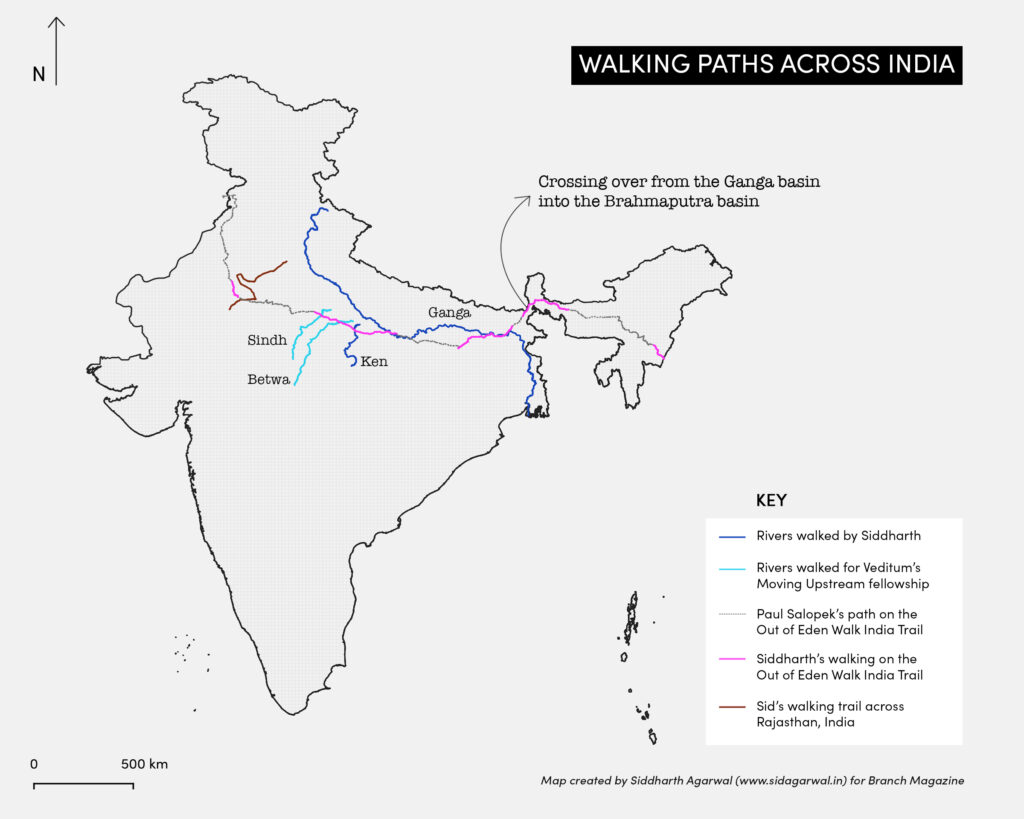

“We’ll soon be crossing an unobserved boundary,” I said to Paul Salopek with whom I was walking across India in 2018-2019 as part of his multi-year, multi-continent project Out of Eden Walk.

Paul began his walk from Ethiopia in 2013 following the footsteps of the first humans who migrated out of Africa in the Stone Age and moved Eastwards. As expected, his walking path meandered, influenced by landscape and climate but also the pushes and pulls of contemporary geopolitics.

Six years on, we were walking together on a tar road passing through the Mahananda Wildlife Sanctuary between Siliguri and Sevoke in Northern West Bengal, India. We were crossing through administrative boundaries, transitioning from the plains to the Himalayan foothills through the Terai landscape and walking this highway that splits a Wildlife Sanctuary into parts. It is the unobserved boundary that governs the fate of every droplet falling on these lands.

We had crossed over from the Ganga river basin into the Brahmaputra river basin. This difference of a few metres decides the journey of every droplet for 1000s of kilometres. They do eventually meet again and flow together, first as Padma and then Meghna, and then into the ocean. The silt and nutrient-laden waters further carve the ocean bed for 1000s of kilometres all the way down to South East Asia.

This ocean is heating up in an otherwise natural cycle accelerated by human activity. This is an effect of what we commonly call “climate change.” This change, brought into effect by our species, is cracking open boundaries, creating rough edges, and increasing inequality.

Though this is often spoken about as a collective crisis brought upon this earth by the human species, to which we are responding together, my walks over the past 8 years have shown me how the responsibility of its creation and management cannot be divided equally amongst all. Even a cursory look at world history and centres of material accretion is enough to make this amply clear.

Human beings have co-existed on this earth for millennia, but it is the advent of capitalism and colonialism that has predominantly caused the climate crisis and ecological destruction. As for responsibility, it’s abundantly clear that the “developed” Global North that colonised and extracted labor and resources from the Global South to gain wealth, holds much responsibility.

In our current world, most information travels through “controlled highways on the internet” and our physical bodies move mostly through “infrastructural highways” negating all else that exists outside it. How do we then challenge this centralised control and power, take off our blinders, and imagine a different future?

Slowing down

On my walk along the River Ganga in 2016, I was walking on a freshly laid tar road upon a high embankment along the river. This embankment had been constructed very close to the river and cut the river off from its floodplains. A symbol of development: aerial images of this road would soon be in newspapers announcing the arrival of prosperity to the region. The economic numbers were bound to go up, though disproportionately benefiting a certain segment of society.

I paused to look at some artwork created by kids made using sand from the river bank. Many of them had written their names on the road. An identity marker, claiming their piece in this large pie, only to receive their share of the economy when national or state level numbers would be divided to create ‘per capita’ figures. Nothing tangible would come of it. This is the myth of trickle-down economics, where those who are at the bottom of the pyramid often receive benefits only in official records, sitting in the denominator. It doesn’t have to be this way but continues as an outcome of our current models of thinking.

Like highways, the internet too has a huge potential of distribution, only if such an intent exists. How then, do we imagine this infrastructure differently?

Like highways, the internet too has a huge potential of distribution, only if such an intent exists. How then, do we imagine this infrastructure differently?

As part of my work, I’ve spent the past 6 years walking 1000s of kilometres across India along its rivers and across watersheds. At my organisation Veditum India Foundation, we’ve also instituted the Moving Upstream Fellowship program in partnership with Paul Salopek’s Out of Eden Walk. 14 fellows have walked 1000s of kilometres along two Indian rivers.

Walking and slowing down has given us the freedom to walk away, instead of walking along these highways. Like secondary and tertiary branches on a tree, it has allowed us to walk to the people and ecosystems that keep the larger network alive. Agricultural zones that produce the food, and natural ecosystems that maintain the balance of air, water and temperature. It is difficult to notice these when zipping through on highways, or on the fast lanes of the internet where local contexts are quickly forgotten. This very feature, however, opens up a different possibility too.

Possibilities and pandemics

As we tried to make sense of the world when going through the pandemic in the year 2020, the Indian Government proposed amendments through the Draft Environmental Impact Assessment notification 2020 (Draft EIA 2020) that would change the if, how, where and when of environmental and social impact assessments in this country. If anything, the rolling out of the proposed amendment was a precursor to the future, on the way to-be-impacted communities would be consulted and evaluations carried out. There would be none.

In the absence of the possibility of physical meetings during a pandemic, and no consultations planned by the government itself, “responses” to the draft were apparently sought from those who had access to the internet and were able to read English (the only language in which the document was published) and the privileged (those without privilege found themselves struggling to make ends meet in the absence of state support).

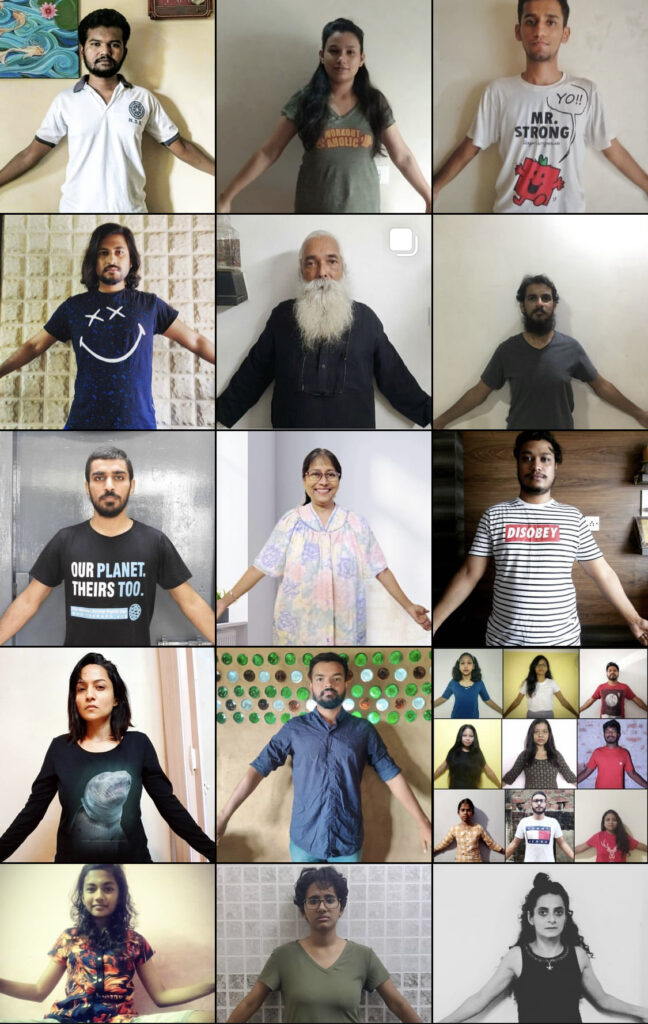

Members of environmental and social movement groups including Let India Breathe (LIB) & Fridays For Future (FFF) quickly mobilised, building solidarity across the country at various levels to challenge this notification and bring forward as many diverse responses as possible. Groups translated the document into regional languages, challenged the proposal in court, mobilised and agitated in every space available (particularly online in the early days of the pandemic) and managed to win small and big battles in the process.

But not without being labelled as ‘terrorists’ by the state itself.

In her book Hope in the Dark, Rebecca Solnit writes, “After a rain mushrooms appear on the surface of the earth, as if from nowhere. Many do so from a vast underground fungus that remains invisible and unknown. What we call mushrooms, mycologists call the fruiting body of the larger less visible fungus. Uprisings and revolutions are often considered to be spontaneous.”

While triggered by a rain of worry, movements such as the one against a deeply unfair Draft EIA 2020, mushroomed on the back of networks of solidarity that have slowly been built over the years. Organisations and individuals work away on problems slowly, working with disadvantaged or marginalised communities. Of course, these movements and their networks are not 100% perfect. As a member of the privileged section of Indian society and a fortunate member of these networks, issues of representation on the lines of class, caste and gender are quite apparent. But the incredible feature of these networks is that they are constantly evolving, and large overhauls from the climate and social justice lens’ can be clearly seen.

Mutual aid and the open future

These networks of solidarity had to continue working overtime throughout the pandemic. The state was often found absent from all spaces. We made it through these times, unfortunately with huge and disproportionate losses, with the help of these and new networks of solidarity, functioning on the concept of mutual aid. A lot of this happened without thinking of the concept of mutual aid, but the principles, guided by these networks as well as people’s basal instincts, came into play.

As we move ahead trying to resolve our challenges with a changing planet, mutual aid and attribution may be our keys to an equitable future. While mutual aid and cooperation are still understood widely, attribution is not. But thankfully, it has come into the popular discussion in recent times, thanks to the tiring efforts by many named and unnamed contributors.

We are often quick to attribute success, knowledge and profits to traditional centres of power and individuals, giving them more power, while we average out failures and losses, so that it becomes a ‘per capita’ figure, where accountability is difficult to assign. These are relics of the past, of kingdoms and colonies, where creators & producers were in the background, serving their rulers. These ideas should have no place in modern times and are correctly being challenged.

Our modern systems of capital and power incentivise decisions to be made on the profit motive, centralisation and control. Our agreements to these contracts have led us to the current climate crisis where the blame keeps shifting, often taking the shape of racial policies and narratives.

In a just and equitable future, borrowing from the values of ‘open’, we will create access for all. It will acknowledge every node that makes a system possible, that creates knowledge, that brings energy, that adds value. And ensuring that the rewards are distributed, equitably and fairly.

An open future holds the promise of decentralisation and mutual aid, but it needs accountable state responsibility. It would be unfair and impractical to suddenly ask people to solve these problems that need solutions at scale. An example of this is the hyperfocus on “individual action and personal carbon footprint,” shifting the guilt to the single ordinary citizen. We must demand more from our governments and corporations while we ourselves live a life in tune with our principles.

An open future holds the promise of freedom, for every drop of rain to enjoy its journey no matter which side of the ridge it falls. To accumulate experiences and reach the ocean, collectively contributing to the rise and fall of oceanic temperatures, and forming grooves into the earth’s crust itself.

About the author

Siddharth Agarwal has been walking across India along rivers, trying to document and bring stories of marginalised people and the environment into the mainstream. His organisation Veditum India Foundation (@veditum) hosts some of his work, along with efforts towards environmental research, documentation, and accountability initiatives. Siddharth is also a steering committee member at India Rivers Forum. He can be reached at [email protected]