Despite waves of environmental movements, climate change remained a relatively economically, politically and socially marginalised issue until recently. Climate activists weren’t able to gather the resources — diverse perspectives and skill sets as well as material support — needed to secure sufficient political and social buy-in for meaningful change. For this reason, climate scientists nobly rose to the challenge of also communicating the science to the public. But communications is its own science, and scientists were not only taking on a role that was out of their comfort zone, they were also up against well-funded disinformation campaigns and lobbying by the fossil fuel industry.

Full-time climate communications work is no longer a rarity. Yet as a relatively new career path, it’s full of uncertainty, with a need to experiment, ‘feed’ on errors, learn quickly and iterate. Focusing on practice offers the chance to correctly position knowledge as cumulative and up for revision. It provides an opportunity for an honest reckoning with human cognitive limitations, an approach that is in sync with a world that, with every passing shock, seems to be demanding we adapt to it.

“Climate change: The worst story ever. It’s ubiquitous, but very hard to pin down. It’s being caused by everyone and everything. It’s sort of everything and nothing.”

Elizabeth Kolbert, Environmental journalist and author of The Sixth Extinction

The IPCC report says: “Limiting global warming to 1.5°C would require rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.” While this is a daunting task, the good news is science has already revealed helpful actions we can take to foster a low-carbon future. Tree planting, keeping fossil fuels in the ground and transitioning to renewables, like solar and wind, as well as transforming how we grow our food and what we eat, for example, by increasing the proportion of vegan food in our diets, and radically decreasing consumption are just some of the many ways we can lower greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity loss and climate change.

So what’s stopping us?

To change everything, we need to change ourselves. We need a new story about who we are.

Engage with people on their ground and on their terms

25 years ago, Susan Joy Hassol was working with climate scientists on translating their findings to the general public when no one else was.

Hassol says scientists use words the public uses, but to mean different things. For example, scientists often use the term ‘positive feedback’ which the public might associate to receiving positive feedback on a job well-done. However, scientists use this to describe a vicious cycle in the climate system, whereby warming causes even more warming. Hassol has identified 150 words and expressions that create differences between the science and how it’s perceived by the public.

Additionally, when scientists talk about climate models, people can get lost in the details. That’s why it’s advised to anchor communications in the core facts. For example, you might say the following:

“Global warming is an increase in the Earth’s temperature, which changes climate patterns.”

“Warming happens when heat-trapping gases are released into the atmosphere, for example, by burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas for energy.”

“We’re seeing the impacts now, in more frequent and severe heat waves, wildfires, droughts and floods.”

These are a few guidelines for communicating climate science that have been found to work well:

- Communicate using plain language

- Be concise and get to the point quickly

- Repeat the same messages

- Connect felt effects to climate science

- Stay positive

- Use trusted messengers

- Communicate using memorable stories

- Use visuals, humour and other creative forms of engagement

- Encourage dialogue

Climate communications research finds that certain words and concepts have negative associations and can make people more resistant to proposed solutions. Especially if they’re associated with politics they don’t agree with. Some examples are ‘regulate,’ ‘restrict,’ ‘cut,’ ‘control,’ and ‘tax.’

What alternative words and concepts can we use then? Some climate communicators suggest using words like ‘entrepreneurship,’ ‘free market,’ and ‘competition’ because they’re well-received by the public. But this example reveals the largest challenge climate communicators face today: How can we motivate people using words they connect with while also challenging the status quo — that is, the extractivism, competition and consumerism driving climate change? How do we inspire new and necessary sustainable ways of being?

If you pander to comfort zones, nothing changes. If you present something alienating, people dig their heels in and — nothing changes. In this line of work, these missteps can literally feel like the end of the world. But they will and must happen. As was mentioned earlier, this discipline is new and there are no silver bullet communications strategies. There’s only humility, learning by doing, near-constant iteration and humble successes. For now.

But we’re not totally in the dark. There’s evidence supporting the idea that messages resonate more with people when they connect to them personally, to their identities, values, worldviews, etc. Climate Outreach is an organisation specialising in how to engage hard-to-reach audiences — developing climate connection programmes with communities such as youth, centre-right, faith and migrant groups.

Climate Outreach says there are different ways to understand your audience so you can tailor your messaging. For example: surveys, focus groups and stakeholder engagement. Additionally, testing strategies, narratives and communications materials with a sample of your target audience helps gauge reactions and avoid backlash.

Climate Outreach’s Global Narratives Approach is the first initiative to develop communications methodology to build capacity in specific locations; to train local organisations in testing and developing effective climate communications in any setting, including the Global South, which has been particularly neglected in this regard. Climate Outreach’s Global Narratives workshop leads participants through a series of questions:

- Values: What do you care about? What do you dislike? What makes you proud of who you are?

- National identity: How do you feel about your country and your place in it?

- Changes: What changes have you noticed and what concerns do you have for the future?

- Climate change: What does it mean to you and what do you think causes it?

- Climate change impacts: What are the impacts and how will you and others cope?

- Renewables: What do renewables mean to you and can they replace fossil fuels?

Finding that images of polar bears, melting ice caps and smoking chimneys were relatively ineffective at connecting with people, Climate Outreach realised that developing a captivating, diverse and people-focused visual language was necessary. They developed the Climate Visuals website to support journalists, researchers, campaigners, photographers and filmmakers in telling powerful new visual stories — with local flavour.

Navigate everyday conversations

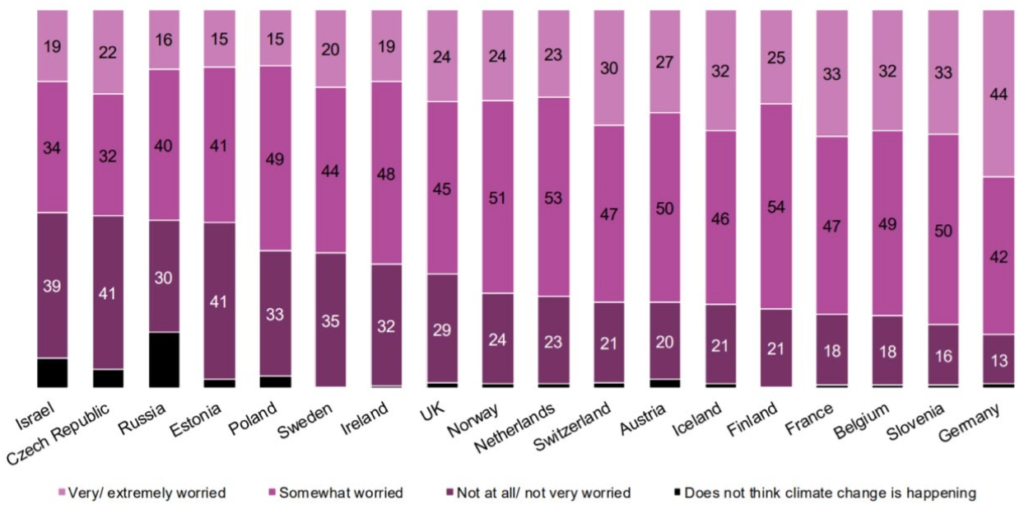

The vast majority of Europeans are very slash extremely worried to somewhat worried about climate change. Yet many people don’t talk about climate change — often, or even, ever — in their daily lives. In America, 60% of people say they “rarely or never” discuss it with family or friends.

We’ve seen using “trusted messengers” recommended a few times now. Arguably, the most powerful incarnation of this is peer-to-peer communication, talking to partners, friends and family members about climate change. Climate Outreach’s #TalkingClimate Handbook, supported by EIT Climate-KIC, was designed to help people have conversations about climate change in their daily lives.

The #TalkingClimate Handbook suggests you use ‘real talk’ in these conversations:

- Respect your conversational partner and find common ground

- Enjoy the conversation

- Ask questions

- Listen, and show you’ve heard

- Tell your story

- Action makes it easier (but doesn’t fix it)

- Learn from the conversation

- Keep going and keep connected

These may seem like obvious recommendations but what they really are, are ways to ensure you maintain a good faith conversation. Once good faith is lost, a conversation on climate change may have the opposite of your intended effect, pushing your conversational partner further into skepticism or denial.

“Nothing that we do — no matter how brilliant, how technologically innovative — can reach the traction and impact that we need it to be… unless we begin to very rapidly skill-up our insights and capacities for understanding the psychological dimension of climate change.”

— Renee Lertzman, Psychologist

EIT Climate-KIC offers a free online course, “Engaging people on climate change.” It was co-created with Dr. Renee Lertzman, who has focused on psychology and climate change for a few decades now. The course identifies ways people confront climate change information at a psychological level and how climate communicators might help them move past their defence mechanisms.

People’s powerful responses to climate change can interfere with their ability to take action. When presented with challenging information that clashes with who they are and what they care about, people can have feelings like guilt, shame and powerlessness. Such feelings can trigger internal conflict, like cognitive dissonance, and defence mechanisms including denial, disavowal and rationalising.

Traditional communications approaches like educating, cheerleading, enticing, nudging, fear and the ‘Righting Reflex,’ that is, the strong urge to tell people the solution to their problem because we feel we know what would work, can be counterproductive. They can trigger defence mechanisms. We need to start having conversations that take a human or society-centred approach. This could entail, for example, making a reflection or summary of what your conversational partner is saying, emphasizing whatever talk of positive change you’ve heard and asking for clarification thereby avoiding the ‘Righting Reflex.’ The goal is to have your conversational partner fit climate action into their life in a way makes sense for them, not for you to do it for them.

Guidelines for connecting with individuals

These are some general guidelines for connecting to individuals that have been found to work well:

- Understand what the audience knows and doesn’t know

- Identify their identity, values, worldviews, beliefs, attitudes, etc.

- Connect with what matters to them

- Use a shared language

- Use trusted messengers

- Frame climate change as personally relevant and provide tangible examples

- Help them realise what they can do and key actions they can take

Part Two of this article will be published in the next issue of Branch.

Further Reading

Watch Christine’s full talk on twitch.tv

About the author

Christine Larivière is a digital communications strategist, manager, and analyst with a data-driven approach who’s working on climate change mitigation and adaptation.