Education plays an important role in leading the upcoming green digital transition. Soon, being green-literate will be quintessential to the development of software systems at any scale. Join the group of innovators of this green transition and get started in measuring the energy consumption of software applications.

Developing green software is the new tech skill that is becoming more and more important. The ambition to achieve climate neutrality is being set by many public- and private-sector leaders and it is clear that the tech sector has an important role to play here. Soon, every tech company will have to embrace the green digital transition and ensure that energy-efficient software is an essential part of this transition. This article helps developers and computer scientists, as well as the code curious, learn how to measure the energy efficiency of software running on their machine and understand how that fits into an emerging green software development practice.

Before we are able to normalise green software, we need everyone to be able to speak greenish. We will never get there if our engineers, scientists, designers, marketers, and so on are not knowledgeable about the foundations of energy and carbon efficiency. If everyone is able to measure and interpret energy data from their software, energy efficiency will be inherently considered in software development activities. As usual, education is key.

Nevertheless, for a long time, energy efficiency and sustainability were never really part of the curriculum of computer science programmes at universities. The only thing that can somehow resemble energy efficiency is performance: students usually show a natural satisfaction in making their code execute in the least possible time. Unfortunately, this enthusiasm of students about making the code more time-efficient is not observed for energy efficiency. Although students are usually interested in learning about the sustainability of software engineering, there is a steep learning curve that needs to be overcome. As opposed to analysing and measuring time, which is simple and accessible, energy data is everything but that.

In that sense, we need to give it a little push before we can have everyone fluent in “greenish”. Hence, universities are pioneering new courses on sustainable software engineering. That’s the case of the Delft University of Technology, which will have its first course on software sustainability already starting in this academic year1. It will cover topics such as green AI, carbon-aware computing, energy-efficient mobile development, and so on.

But of course, the change cannot only happen with the new generation of tech developers. We need to embrace the green digital transformation at all levels. Tech professionals are already used to constantly re-educating themselves on the latest new tool or technique. Unfortunately, there is not a lot of content when it comes to the development of energy-efficient software applications. We need more tutorials, discussions, data, tools, and ideas!

Where do we start?

As always, we need to start small (think big ?). One of the first things that we, green software enthusiasts, need to learn is how to measure the energy consumption of software. This one skill will help us start making energy-aware decisions when developing software. If we know that by adding a new feature, we significantly increase the energy footprint of our software, we will probably consider greener alternatives that deliver the same user experience. Moreover, if our colleagues are also testing energy consumption, we will be able to learn the do’s and don’ts of green software development from each other.

Imagine, for example, that you decided to measure the energy consumption of your online video calls. The results show that, amongst your favourite video conferencing apps, there is one that is consistently more energy-efficient than the others by 20%. This new information would naturally change your behaviour as a software user: you would probably start opting for the energy-efficient software in most of your calls. The same happens at the software level. Imagine that you need to decide on a new library to add to your software project. If you have the means to reliably test their energy efficiency, this will probably affect your decision.

The problem is: we have no clue about the energy consumption of our software and, most of the time, we don’t know how to collect energy data. That’s why we need more developers that know how to measure energy consumption. That’s the first step to include energy in all our decisions as developers and, eventually, make green software development the only software development we know.

Hence, in this article, we will see how to prepare our machine to collect reliable energy measurements and how to use a tool that actually collects energy data from most ordinary personal computers.

This is a twofold problem.

First, there is a myriad of factors that affect energy consumption, making it difficult to compute the exact energy consumption. This is especially worrisome when you are comparing different versions of a given software – you need to make sure that you are comparing the energy consumption entailed by your software and not by anything else running in your computer.

Second, there are many tools out there, but there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Some tools only work with specific operating systems, hardware, etc.

What Do We Need To Fix Before We Start Measuring?

Let’s start with the list of things you need to fix before starting measuring:

- Stop all unnecessary tasks ??♀️. Before measuring, all other applications should be closed, notifications should be disabled, only required hardware should be connected and, if you don’t need internet for the measurement, your computer should be offline.

- Freeze your settings ?. Sometimes, you cannot completely stop all the things that are unrelated to your software. Hence, make sure you freeze all the settings – for example, the brightness of your screen should be the same in all the measurements.

- Warm-up your setup ?. Energy consumption is highly affected by the temperature of your hardware. Hence, always do a small warm-up before running experiments.

- Sleep between measurements ⏸. After the execution of a given program, your computer will still incur residual energy consumption that stemmed from its execution. This is commonly named tail energy consumption. To prevent the tail energy consumption from affecting the results of a subsequent execution, do a short pause between measurements.

- Control room temperature ?. The temperature affects energy consumption. Hence, make sure you have the same room temperature for all the measurements.

- Repeat measurements a few times ?. Despite all efforts to avoid errors, energy measurements are still prone to random variations. This means that it could happen that a new version of your software is perceived as more or less energy efficient just because of these random variations in energy consumption. The only way we can fix that is by repeating measurements until the results look consistent. This is illustrated in the animation below: the first measurement indicates that version

Bis less efficient thanA; after repeating the measurements, we see that versionBspends roughly 20 joules less thanA.

Plot of the distribution of energy consumption for versions A and B. In each iteration we add another round of measurements (depicted with the new blue circles). When we reach iteration 30, it is clear that version B is more energy efficient. On average version A uses 100 joules and version B uses 80 joules, yielding a 20% improvement. View source.

- Create automated executions ?. If we want to repeat measurements, they should be repeatable. No better way to do this than by automating executions. This is typically done with common software testing tools.

- Shuffle measurements ?. Instead of executing all the measurements for a given version and then all the measurements for another version, it is recommended to randomly shuffle the executions. This way, we prevent any unexpected (yet unnoticeable) measurement error from affecting only one of the versions being tested.

Keep in mind, though, that these guidelines should not discourage you from measuring energy consumption. My advice is that you start simple – no automation, no repetitions, etc. – only a simple first result to give you some intuition. That is more than enough to start discussing the energy consumption of your software and to get your colleagues into it.

Nevertheless, if you really want your team to use energy results consistently, you will eventually need to cover all these guidelines. Failing to adopt them will lead to something that software engineers often call flakiness: when two executions of the same test produce different results. The problem of flaky tests is that developers will stop worrying when tests fail – making tests useless. And we want the results of energy tests to be taken seriously.

Let’s Start Measuring

Now that we know all the basics about measuring energy consumption, there is one last thing that needs to be mastered: the collection of energy consumption data. In the old days, one could only measure energy consumption using special hardware with physical power sensors. Today, we have several tools that provide reliable power estimations. That’s the case of Intel Power Gadget, which is the easiest and most accessible energy measurement tool I have come across. It provides a handy graphical interface, and anyone can use this tool with only a little tech skills.

Here’s how to use it:

- Install it ?. via the official website:

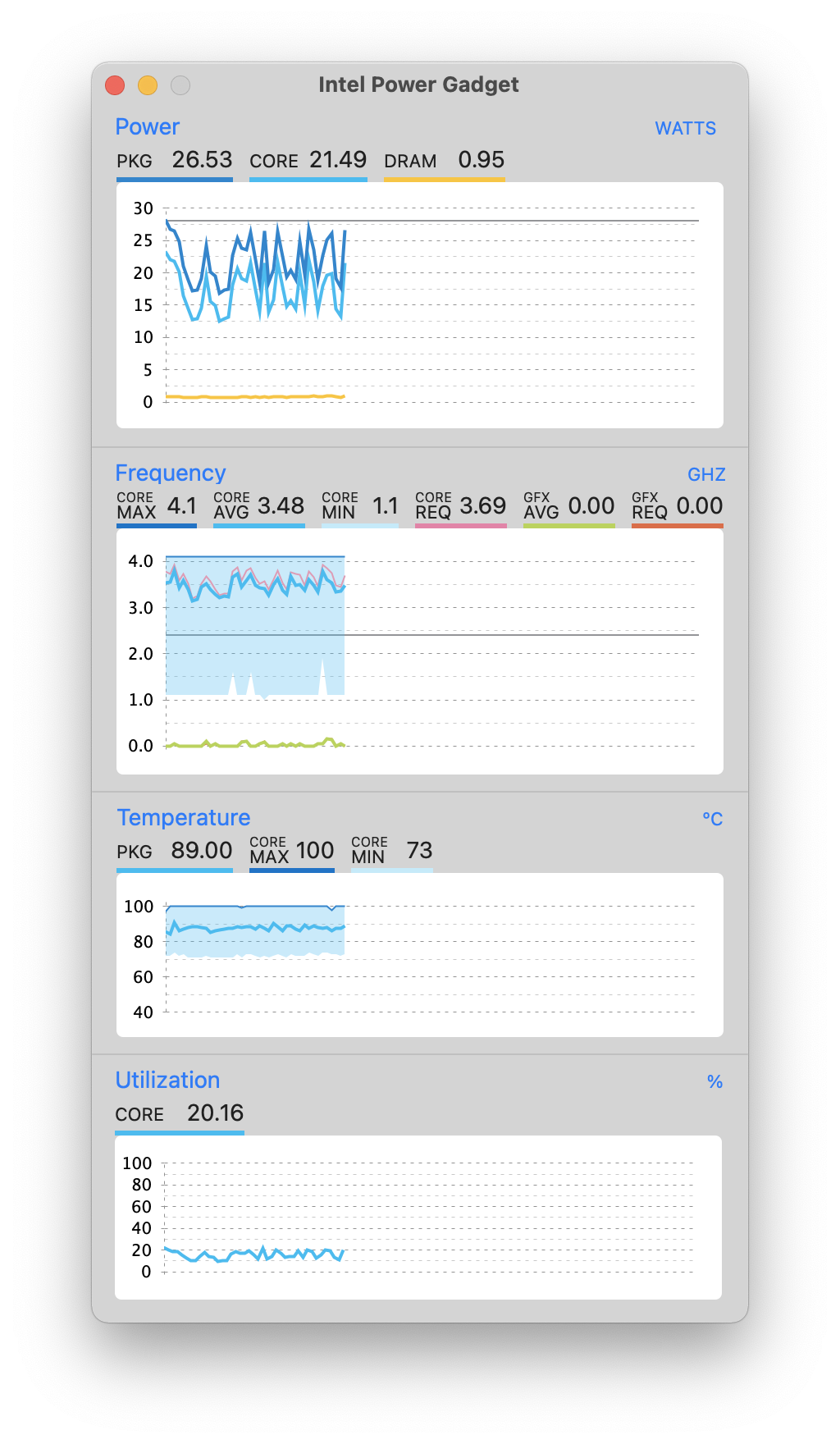

https://software.intel.com/content/www/us/en/develop/articles/intel-power-gadget.html - Open it ?. The interface shows a few plots with

CPU utilisation (%),Frequency (GHz),Temperature (ºC), andPower (W).

- Start collecting ?. You simply have to click on the menu

Logging > Log to Fileto start measuring (and once again stop it).

- Check results ?. The power data will be collected and stored in a

CSVfile under your Documents folder (default behaviour). I have run a small test and, in my case, it was stored in~/Documents/PwrData_2021-2-19_17-16-10.csv.

When we open the CSV file – using, for example, Excel – you find several columns. Some are straightforward – e.g., System Time, Elapsed Time (sec), Processor Power_0(Watt) – while others tend to be more complex – e.g., RDTSC and GT Requsted Frequency(MHz).

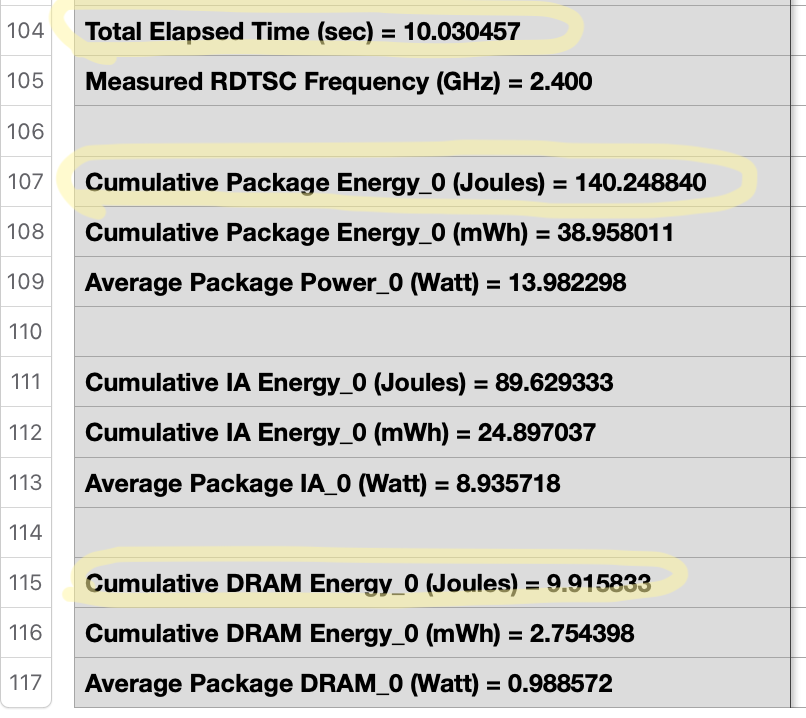

Let’s not worry too much about it. If you scroll all the way down to the bottom of the file, there is a summary table with a few important attributes:

- Total Elapsed Time (sec). The total time in seconds in which power data was being collected.

- Cumulative Package Energy_0 (Joules). The total energy consumption of the processor.

- Cumulative DRAM Energy_0 (Joules). The total energy consumption of the volatile memory.

And that’s it! You have made your first energy measurement! Now, go ahead and start measuring the energy consumption of your favourite apps. For example, what is more energy-efficient: a 10-minute call over zoom or the same call over Microsoft Teams? Browsing the Web using Chrome or Firefox? Listening to your favourite song on Spotify or Apple Music? Watching Netflix or HBO? The possibilities are endless.

Keep in mind, however, that the main strength of the Intel Power Log is also its main weakness: the graphical interface is really easy to use but it is not so simple if you want to automate executions. Command-line interfaces are more suitable for automation. There are a few alternatives out there – check my previous article on energy tools2 if you want to try a different energy measurement tool.

Finally, keep in mind that measuring energy consumption from your computer is just a piece of the puzzle. Much more goes into the energy footprint originated from our activity in front of the screen. Cloud servers, internet providers, and so on, all work so well that we have no idea what exactly happens beyond our desks – including the total energy being used. Yet, this is the first step to get everyone involved and have all the techies talking about energy efficiency.

Good things lie ahead if we all start measuring energy consumption: energy tools will have a bigger community of users, will improve their usability, their compatibility with different hardware, and so on. The more we democratise energy measurements, the more green-literate engineers will be working in the next generation of software systems, AI applications, cloud services, data centres, and so on. Eventually, green software development will be the only software development we know.

Further Reading ?

If you are interested in the topic, here are some useful resources available online:

- Sustainable Software Engineering. Syllabus and materials of the course at the Delft University of Technology. ↩

- Tools to Measure Software Energy Consumption from your Computer. Alternatives to Intel Power Gadget with quick-start steps. ↩

- Energy Patterns for Android Applications. A catalog of 22 design patterns to develop energy-efficient mobile apps. Although these patterns were tuned for Android apps, they might inspire you on energy-efficient solutions for your server/desktop software projects.

- Green AI – Annotated Bibliography. List of academic publications that focus on the carbon-efficiency of AI systems.

ABOUT AUTHOR

Luís Cruz is an Assistant Professor at the Delft University of Technology and the Scientific Manager of the AI-for-Fintech Research lab. He holds a Ph.D. in Computer Science from the University of Porto, Portugal.

Luís has been actively contributing to the research fields of AI-Ops and Sustainable Software Engineering, aiming at defining software engineering practices for AI projects and at improving development processes to deliver carbon-efficient software. Luís personal and professional goal is to make all AI models climate neutral.

When Luís is not working, you can find him surfing the Atlantic waves, dancing Lindy Hop, or simply enjoying a croissant with a nice cup of coffee. Feel free to reach out on Twitter (@luimcruz) or check his website: https://luiscruz.github.io/.