My name is Dennis “Bumpy” Pu‘uhonua Kanahele. I’m the head of state of the nation of Hawai’i. The journey for me started back some 40 odd years ago. It was in 1978 that the Hawaiian culture was starting to rise up. During that time, there was a state constitutional convention which created the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

Can you imagine not knowing anything about your culture, and all of a sudden, there’s this rush of information, of history, that’s starting to come in, and it’s all very foreign to us. We were absorbing a hundred years of our history in a short time and trying to understand what happened.

And so in 1980, the first trustees of this office ran, and I was one of them. I just wanted to get involved. It was the reawakening of our culture.

Thirteen years later the Apology Law came into effect. It acknowledges the overthrow of the Hawaiian government a hundred years earlier. That law was signed by the President of the United States in 1993. In November, Congress passed it: both the House and the Senate.

I was appointed that same year, in July 1993, as a Sovereignty Advisory Commissioner, for the state of Hawaii. Then we faced a decision: now that the United States finally apologized to the Native Hawaiian people for their participation in the overthrow, the Hawaiian people can now proclaim the restoration of our independence—should we decide to. That was a heavy heavy thing. I was a commissioner hearing that legal opinion. So I was like, holy smokes.

We learned we could craft a constitution based around the ohana and the family system. So that’s what the elders did. On January 16, 1994 we proclaimed the restoration of Hawaii’s independence. I was appointed the temporary head of state for the nation of Hawaii. We went right into constitutional convention.

And oh my goodness, to watch 70, 80, 90 year old elders actually figuring out what civil rights mean, what enumerated rights mean, what is a judiciary branch, what is an executive branch.They crafted a constitution in one year. It had a general Legislative Assembly, made up of Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian. And they set up the judiciary branch, the tribunals side with only Hawaiian, and the elders would be the enforcement side of the nation.

Believe it or not, it became a sustainable act by putting the elders there. Because our children would become elders. And so it becomes a sustainable way to hang on to things that were stolen in the past.

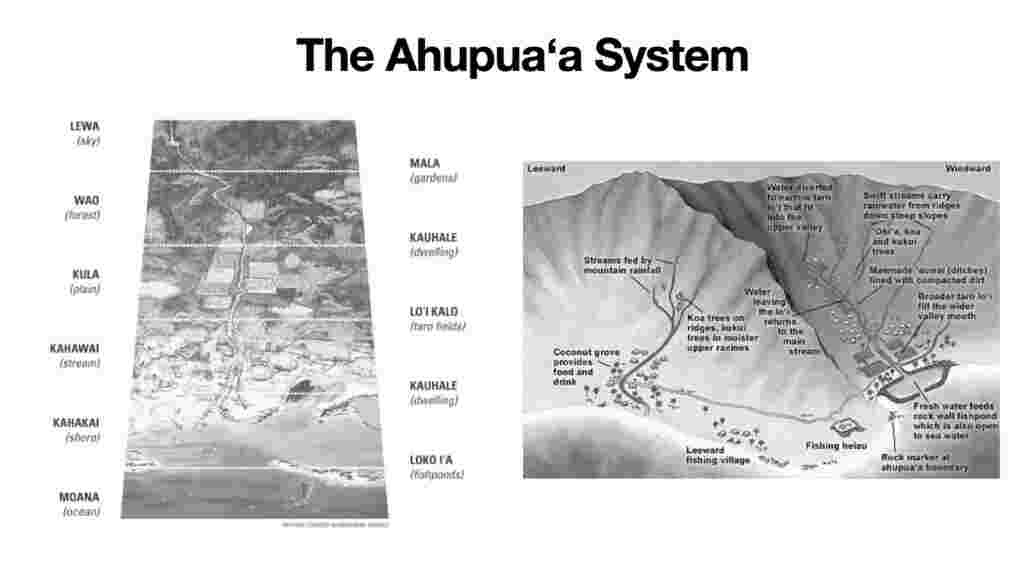

Sovereignty and sustainability are who we are. The connection between sovereignty and sustainability is like brother and sister, the past and the present, AHUPUA’A!

Now, I can go into all kinds of stories that happened from 1995 on. It was really a push and pull thing with a government. I got arrested and treated as if I was going through an apartheid kind of situation. I started to participate in state functions just so that I would show the initiative of trying to unite us, no matter what the government did to me, like putting me on probation for three years. We had the land, but we didn’t get a lease until 2001.

The state gave us respect, not as squatters, but as people that were wronged a long time ago. And we’ve been trying to restore some sense of what belonged to us. That is what a nation is, that is why the nation was created. Because we knew that if we didn’t do it, then it would probably be so hard right now to do what we did all these years. We had no help from the state, no federal government funding. Nothing to really take us to the next level.

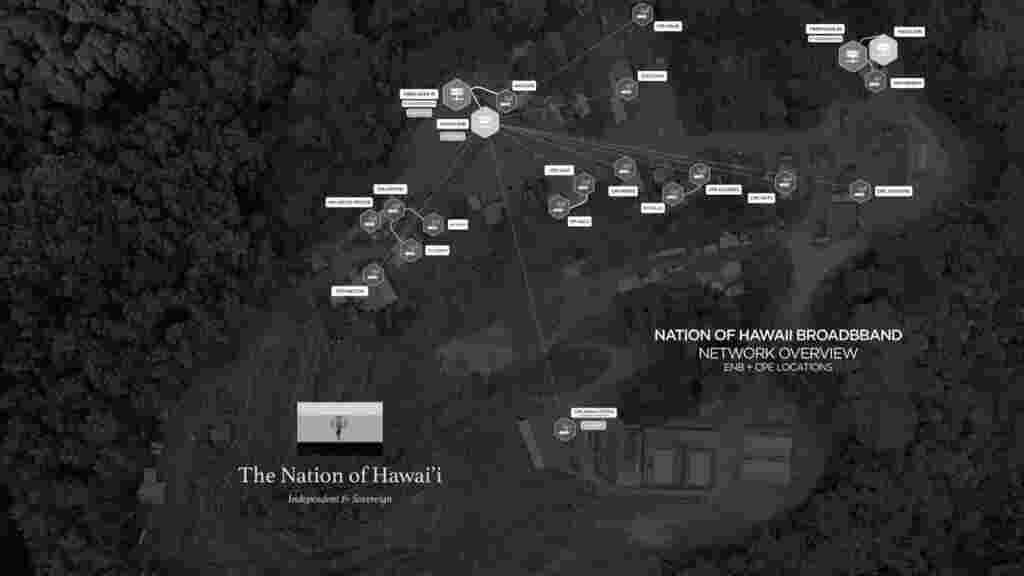

That changed in 2018. A community internet project is the first project that we had working with the State of Hawaii government. And we did that through the blessings of Internet Society and Mark Buell. And we worked with the Hawaiian Telcom, agencies we never got along with earlier, because of the political stance we took and things that were done years prior that brought us to this point.

But it was a whole new journey, because the state needed a pilot project. And we never worked with the state. And so, we ended up trenching the trenches, laying the lines and working with experts in broadband networks.

And they came in heavy. They showed us how to wire up the connections. And we started to help put them up and really dig in. What we were doing, unbeknown to us at the time, was actually becoming our own internet service provider.

And I tell you, I wouldn’t buy a service from us right now. Because we’re still in the learning parts of connectivity. But we’re working at it.

But you know, once you get broadband, you want more speed. And we’re learning how to regulate the speed and all that stuff now. And internet access is a human right. That is a sanction from the United Nations.

So, some of the hardest things are not so much our technology and hardware, but getting the right people to care for it. And so we are really excited about the relationship that we’ve carved out with the connection of broadband. I think that was what made us trust working with anybody after that.

Sovereignty and sustainability are who we are. The connection between sovereignty and sustainability is like brother and sister, the past and the present, AHUPUA’A!

We had a system called the Ahupua’a system. The water system was how the water flowed from the mountain to the ocean. Now, that water from the mountain to the ocean was maintained—it was managed. That was our system, we managed the system. And we were so in tune with Mother Earth. That’s basically what aloha meant to us. Our ancestors had to maintain the waterways in the mountain, and the flow of the streams down to the ocean. So they would make taro patches and fish ponds along the way down to the ocean. And the sustainability of that was not just the human beings, but all the fish and all the things that would spawn and would come in from the ocean and swim upstream.

We try to use sustainable technologies. Because Mother Earth is still giving us a chance, we should be fortunate.

This is what restoration of independence means to me, for our country. And using technology like broadband and communications and all these other good things to speed up the restoration process of the oceans and of all animals that run in oceans.

How can we sustain ourselves? How can we bring sustainability back?

This is what restoration of independence means to me, for our country. And using technology like broadband and communications and all these other good things to speed up the restoration process of the oceans and of all animals that run in oceans.

The Hawaiian people have never given up on Aloha.

About the author

Dennis “Bumpy” Pu‘uhonua Kanahele is the head of state of the nation of Hawai’i and founder Pu‘uhonua o Waimānalo, a Hawaiian cultural village and traditional agricultural restoration project in Waimānalo, Hawai‘i.